Quick Links

ALFilm Official Website

Fresh perspectives and reliable information about the middle-east are hard to come by, despite the sheer number of reports about the region’s politics and culture which are published every day. Each story gets filtered through the biases and agendas of the news outlet which reports it. Without being able to speak Arabic or having a direct connection to the region, any perspective I’ve been able to gain is inevitably narrow and skewed. Between libraries, conferences and the internet, there are admittedly many places to start gathering information. The daunting part is knowing where to begin searching. This film festival is an event where it’s possible to gain a huge amount of information about the Arabic world in a short space of time. Like all good film festivals, ALFilm is much more than a showcase of related or upcoming cinema. Every film I saw had something interesting to say or a different perspective to offer. Even the films which were fun or trashy had great performances, wry humor or political subtexts.

This year the central theme of the festival was Jewish-Arab identities. Before the festival began I have to confess I had almost zero knowledge on this subject. Thinking about it after the festival, I couldn’t recall seeing or reading anything else which linked these two identities. The films which connected with this subject, overtly or otherwise, challenged the binary view of Arab and Jewish origins as being fundamentally separate (a view I’d tacitly absorbed without properly questioning it). A major highlight of the festival was when this issue was addressed at a podium discussion on Friday night. The debate was heated and complex, drawing on range of history and thinking that I wasn’t previously aware of.

I can’t attempt to recount everything that was discussed, but I believe the discussion was filmed (I’ll add the link here once it’s available online). One part that stuck in my mind was an inspired response from Ella Shohat (someone whose work you should really check out) to a fairly condescending question about the reasons behind migration to Israel in the 20th century. Her answer included one of the best and most methodical deconstructions of Zionism as a philosophy that I’ve heard before. The discussion was a great opportunity to hear a deeper analysis of the issues surrounding the festival films.

Politics and identity were the key themes of the festival, but I was also struck by the unique humor in the festival films. A friend from Egypt once told me that in Arabic comedy, the biggest laughs are usually from jokes about sex. Going by the films I saw, there is some truth to this statement. A good portion of the jokes and comic moments had a distinctly “ooh err Mrs” feel, reminiscent of the British humor I grew up with. However, there was one key difference. It may have been down to the good selection of films, but the comedy was rarely as simple as it initially seemed.

Despite being basic, most of the jokes had political dimensions or were mixed into darker and more sophisticated satire. One collection of shorts by Arabic directors about the first gulf war featured a pointed joke about Israel-Palestine relations which had much of the audience roaring with laughter. This sound was intermingled with gasps at the fact that someone had made such a joke on the big screen. I may simply be unfamiliar with the style of comedy but I found the humor in the festival films was as distinctly funny as it was problematic.

The festival wasn’t without a few minor drawbacks. Last year the majority of the films played in one place (Babylon Kino). If you had the stamina you could see just about everything. The screenings were spread across four different venues. I discovered a few indie-Kinos I didn’t know existed, but I also had to dash between the venues a lot or spend a long time choosing which films I would have to skip altogether. It was tough to decide where to go each evening. One other problem was more bizarre: a few screenings had multiple groups of people loudly chattering all the way through the film. I even picked up my first piece of Arabic from a co-worker after one screening - I learned how to say “please be quiet”.

Despite a few hitches this year I really enjoyed the festival and would highly recommend it to enjoys good cinema or wants a deeper insight into the issues which affect the Arabic world. The festival pass cost only 50 euros for which I got to see 12 films in 7 days. I also gained a significant amount of new knowledge and discovered new people and filmmakers to read up on. ALFilm remains a major highlight of the film calendar in Berlin.

Blind Sun

In the blazing heat of Greek summer, a solitary man named Ashraf arrives to take care of a villa whilst its rich and snooty owner is on holiday with his family. Instantly victimised by the locals for his Arabic origins, Ashraf’s isolation becomes progressively more extreme. The rising heat leads to a drought which quickly gets out of control. Water rationing begins and Ashraf’s presence in the grandiose house begins to draw further anger from the locals. Isolation begins to take its toll on Ashraf’s mind and he is unable to shake the feeling that he may not be alone in the house.

The cinematography in this film was really stunning. The whole film created a rising sense of unease and separation from reality. Ziad Bakri gives an excellent portrayal of Ashraf whose tough exterior hides vulnerability and paranoia. The artful shot composition and highly creative camera angles created a constant duality in which the Greek countryside was both beautiful and overpoweringly intimidating.

Some of the creepiest moments were in the house during the night-time scenes. The deft use of lighting tricks and carefully cast shadows transformed the previously opulent setting into somewhere that instantly felt unnatural and claustrophobic. After having seen so many horror movies in the past, this a film that can pull off these effects enough to genuinely unnerve me is a rare treat. The entire movie reminded me of Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining and some scenes even felt like they were referencing it directly, especially as Ashraf’s mental state begins to deteriorate.

Whilst this film was a festival highlight, I couldn’t escape the feeling that I’d missed some key references to wider events in Greece. Water is constantly foregrounded throughout the film but it plays an oddly ambiguous role in the plot whose greater meaning passed me by. The plot itself was also relatively disjointed and as the film reached its climax, I felt like a lot of the tension had already been lost. This wasn’t a perfect film but it was gorgeously shot, featured some inspired performances and achieved the rare feat of being genuinely creepy and unsettling.

Un été à La Goulette

It’s 1967 and in the middle of the Tunisian summer three girls at the edge of adulthood - Gigi, Merriem and Tina - have grown sick of their families’ attempts to control them. The trio’s close friendship is uninfluenced by their backgrounds: Gigi’s family is Christian, Merriem’s Muslim and Tina’s Jewish. The girls swear an oath to have sex for the first time on August 15th (a major religious holiday). Their bond remains unbroken despite their fathers’ vain attempts to break it. August 15th is approaching fast but an array personal and familial problems stand in the way of the girls’ attempts to keep their oath.

On the surface this film is a well-written but trashy summer comedy - there is more to it. The film’s attitude to women is far from progressive but the three main characters are independent and multi-faceted. The leary but hapless boys they choose to fulfill their oath are depicted as falsely believing themselves to be in control when they really function as the girls’ expedient sexual outlets. The film’s subtle interplay with religion and wider issues in the middle east belies its seemingly light-hearted nature.

Much mirth and drama is extracted when as the movie plays on political events or religious sentiments. The girls’ oath is sworn in a catholic church before a statue of the Virgin Mary and there is one memorable sequence in which Merriem deliberately misuses the veil she has been forced to wear. Un été à La Goulette is neither side-splittingly funny or markedly clever in its execution. It was however an unexpected treat which surprised me with its poignancy and intelligent humor.

The Gulf War… What Next?

In 1991, five Arabic directors each produced a film as a reaction to the first Gulf war, resulting in this collection of shorts. Each film was markedly different but only one featured images of the war itself. The majority of the films focused on the wide-reaching effects of the war rather than depicting it directly. What really stood out was the dark and pointed comedy which was present in every short in the collection. One film included a montage of gleefully vile and racist army running chants cut with images of the invasion’s bloody consequences. Others simply cracked politically-themed jokes at the boundaries of good taste. Each director seemed to partly share a wry but tragic sense of humor.

The collection featured two films which were highly personal and introverted in nature. One of these films was about a director who, suffering from writers’ block with the deadline for the film approaching, phones all of his friends in a desperate search for a good concept. Each friend provides an increasingly absurd idea, much to the director’s frustration. Another film simply showed the director standing alone in odd places or isolated corners of his flat, occasionally communicating with his friends via computer or fax machine. Both films were slow-paced and confusing but equally effective in piecing together a feeling of bewilderment and loss.

There was so much to this collection of films that it could easily fill an entire article. Although the shorts from this group weren’t my favorites out of the whole festival, they made for a uniquely strange and frequently unsettling viewing experience.

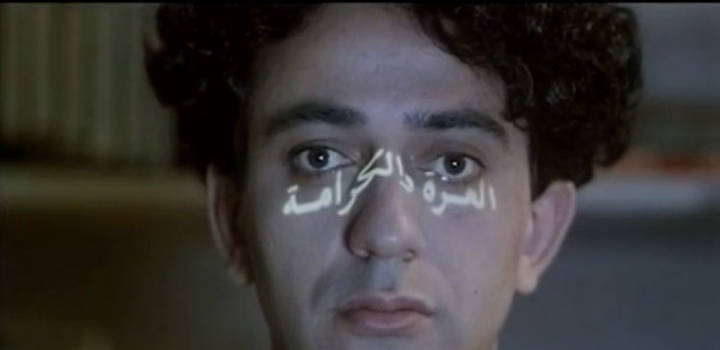

Very Big Shot

Ziad is a small-time drug dealer who operates out of a pizza take-away shop and dreams of better things. When he decides to try and leave the drug business, his boss tries to have him assassinated. Having survived an attempt on his life, Ziad is in a difficult position: he suddenly has a huge amount of white powder and very little time to dispose of it. Short on ideas, a former customer who is also a struggling director puts an ambitious but far-fetched idea into Ziad’s mind. He decides to shoot a film as a cover for exporting the drugs and laundering the proceeds. With his boss on his heels and a hapless but determined film crew, Ziad’s first and only film production begins to take on a life of its own.

Anti-hero characters are never easy to write well. Ziad is greedy, offensive, violent and self-centred. Strangely he still remains compelling as a character due to his extreme ambition and pragmatism. The entire film is a wild ride driven by its protagonist’s search for increasingly outlandish ways to avoid looking facts in the face. Whilst the character himself is unsympathetic in the extreme, the comedy born from his relentless drive and his relative underdog status in the hierarchy of Beirut’s underworld somehow kept me engaged throughout the movie.

An unfortunate problem I have when watching funny or deliberately unrealistic gangster movie is that I can’t avoid a comparison with Guy Ritchie and his dopey films which symbolise this genre. The humor in Very Big Shot isn’t much more sophisticated than Ritchie’s films, but the jokes felt less forced and lazily written. The writing and cinematography interplay excellently in this film to lift it above similar genre efforts. There are a wealth of silly sight gags in this film along with moments where the tension builds right up only to be dispelled absurdly.

For all its wit and self-reflection about film-making, Very Big Shot felt as glitzy and over-driven as its main character. I felt like I may have missed out on some key references to Lebanese politics or culture in Ziad’s unlikely rise to success, but for me the film was simply a lot of fun which fell short of becoming a classic.